As I’ve lamented previously, the documentation for xperf (Windows Performance Toolkit) is a bit light. The names of the columns in the summary tables can be exquisitely subtle, and I have never found any documentation for them. But, I’ve talked to the xperf authors, and I’ve used xperf a lot, and I’ve done some experiments, and here I share some more results, this time for the Disk Usage summary table.

This post was updated September 2015 to include information about UIforETW, WPA, and new columns.

An alternate view of the disk I/O and file I/O tracing with explanations of what overhead is missed (anti-malware!) is available on The Old New Thing, and another article discusses the system process.

Previous articles in this documentation series include:

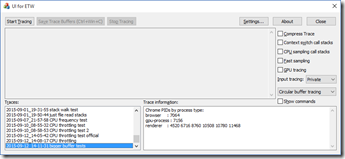

This post assumes that you are recording traces with UIforETW and that the WPA (Windows Performance Analyzer) startup profiles which ship with UIforETW have been installed. You can do this from the Settings dialog by clicking on Copy startup profiles. This post also assumes that you are using WPA 10 to view the traces – this is the default when you double-click on a trace in UIforETW‘s Traces list.

This post assumes that you are recording traces with UIforETW and that the WPA (Windows Performance Analyzer) startup profiles which ship with UIforETW have been installed. You can do this from the Settings dialog by clicking on Copy startup profiles. This post also assumes that you are using WPA 10 to view the traces – this is the default when you double-click on a trace in UIforETW‘s Traces list.

You gotta know when to use it

When profiling I rarely start with Disk Usage because it is usually not directly useful. Having your disk 100% busy is not by itself a bad thing. It could mean that your disk is thrashing and causing an application hang, or it could mean that the OS is lazily writing modified pages back to the disk because the disk is otherwise idle.

The usual way that I end up looking at disk I/O is if I notice a hang. Usually it is an idle CPU hang where the critical thread is clearly waiting on a disk I/O operation such as ReadFile or CreateFile. Occasionally it is a busy CPU hang where the CPU is doing a busy wait until some I/O completes. But I usually wait until I see evidence elsewhere – hey, we’re spending all our time waiting on disk I/O! – before looking at disk usage.

Getting there

In the Graph Explorer on the left of WPA you can double-click on the Storage section to open up the default disk usage graph. ![]() You can then show the associated summary table by clicking on either the first of the five buttons shown here (summary table and graph) or the third button (summary table only). You can adjust the set of displayed columns with the

You can then show the associated summary table by clicking on either the first of the five buttons shown here (summary table and graph) or the third button (summary table only). You can adjust the set of displayed columns with the  View Editor, or by right-clicking on any column to enable/disable columns, and by dragging columns around to reorder them. Rearranging the columns – especially the columns to the left of the orange bar which are used for grouping – is crucial for finding answers to life’s persistent questions.

View Editor, or by right-clicking on any column to enable/disable columns, and by dragging columns around to reorder them. Rearranging the columns – especially the columns to the left of the orange bar which are used for grouping – is crucial for finding answers to life’s persistent questions.

If you open up the Storage section in the Graph Explorer you will see a Disk Usage section, and if you open that up you will see about fourteen different graphs available. These graphs all offer different views of disk usage, but they all offer the same thirty columns in their associated summary tables. The default order for these columns varies, and sometimes the same column is configured to show up twice (once as a Sum and once as an Average), but the summary tables associated with these Disk Usage graphs are all fundamentally the same.

But first, pretty pictures!

Before getting into the dry technical documentation I want to share one of my favorite WPA graphs – the Disk Usage Disk Offset graph. This graph has time along the x-axis (as usual) and the disk offset of disk operations on the y-axis. This means that, for spinning-rust disks, the graph gives a rough approximation of head movement:

I just think that’s cool! Good and bad disk access patterns become clearly visible.

The vertical red-lines are flushes, which are death to disk performance, and the selected region shows why. An application is repeatedly doing writes followed by flushes, and each flush forces a write to C:\$LogFile (the purple dots along the bottom) with an associated seek.

Not all file I/O is disk I/O

It is important to understand the difference between disk I/O and file I/O. In xperf’s nomenclature ‘File I/O’ occurs every time somebody calls one of the file I/O functions such as ReadFile, whereas ‘Disk I/O’ is when the disk actually has to do some work. A lot of file I/O doesn’t result in disk I/O because the Windows disk cache does a great job of keeping things in memory. This cache is the main reason why you can never have too much memory – my 64 GB work machine typically has 45 GB of data cached, which keeps it humming along quite nicely.

It’s also important to understand that, on Windows 7 at least, I/O that goes to the optical disk is not recorded. That’s a shame.

As usual the columns can be configured to be a count, average, max, min, sum, etc., depending on what you need. Just go to the WPA View Editor and change the Aggregation type.

With all that said, here are the meanings of the columns. I’ve grouped them into categories to make the list easier to navigate:

Columns for who is doing the I/O:

- Process – the name and process ID of the process doing the I/O. For many writes this will be listed as ‘System’ because the WriteFile call returns immediately and the system process then writes the data in the background. Reads may be attributed to the ‘System’ process if it is doing read-ahead.

- Process Name – the name of the process, without the process ID. This allows identically named processes to be grouped together.

- Thread ID – the ID of the thread doing the I/O.

- IO Init Stack – if you have asked xperf for call stacks using the DiskReadInit, DiskWriteInit, or DiskFlushInit then the call stacks will show up here. These flags can be specified in the UIforETW settings, under Extra kernel stackwalks. This can obviously be handy for finding out exactly where disk I/O is coming from. However when I need disk I/O call stacks, especially on reads, I can usually find them by doing idle thread analysis.

Columns for what I/O is being done, and where:

- Path Tree – this gives you a tree view of the paths being accessed. This should be placed to the left of the orange grouping bar and you can then expand it like any normal tree control, getting various statistics summarized by partial paths.

- Path Name – this displays the full path of the file being accessed. When placed to the left of the orange grouping bar this lets you group by filename in a non-hierarchical way.

- File Extension – this contains the file extension of the file being accessed, in case you want to group by file extension. This could be useful if, for instance, you suspect that DLL accesses or .jpg accesses are causing problems.

- Disk – the disk number, handy for having in the leftmost column for grouping by disk. Since most machines just have a single disk this will usually contain zero.

- Min Offset – the offset is just a number, in hexadecimal, from zero to the size of the disk, representing the location of the disk access. I think of this as representing the head position (for spinning rust disks) and it is useful for seeing how much seeking is going on. This column shows the minimum offset for all of the operations summarized on the current row.

- Max Offset – this column shows the maximum offset for all of the operations summarized on the current row. For a single operation this will be Min Offset plus Size minus one. By comparing Min Offset and Max Offset for a series of I/O operations you can get a rough sense of how well localized they are, which is important with spinning disks.

- IO Type – this column records whether the I/O is a read, write or flush.

Columns for the performance characteristics of the I/O:

Note that times in seconds always refer to points in time, whereas times in μs always refer to durations.

- Init Time (s) – this is when the I/O request was initiated.

- Complete Time (s) – this is when the I/O request was completed.

- Disk Service Time (μs) – this is the elapsed time to perform the read or write as seen by the disk. The assumption is that a disk can only work on one I/O at a time, or at least a given period of time will only be ‘billed’ to one I/O, so the sum of these can never significantly exceed the length of time being analyzed. The only reason the sum can be slightly longer than the analysis time is because there will often be an I/O that starts before the analyzed region and then completes inside it.

- IO Time (μs) – this is the elapsed time to perform the read or write as seen by the thread initiating the access. It is, roughly speaking, the time that it takes the call to return, and it simply the difference between Init Time (s) and Complete Time (s). IO Time can never be less than Disk Service Time, but because there can be many threads performing disk I/O simultaneously there is no limit to how much greater it can be. For writes – where the I/O function returns before the operation is complete – IO Time is set to Disk Service Time, which means it may overstate the time the thread spends on the disk I/O.

- Size – the number of bytes read or written by the operations summarized in the row. This is one measure of how much work is being done.

- Count – the number of operations summarized on the row. In many cases this is a better measure of how much work is being done than Size. Disks are at their most efficient when doing a small number of large reads and writes – anything less than about 1 MB can be significantly inefficient – and a large number of operations may be inefficient.

- Priority – this is the I/O priority. Most I/O runs at normal priority, but some processes such as SearchProtocolHost.exe run some of their I/O at Very Low priority in order to avoid interfering with foreground tasks. Other priorities are possible. I/O priorities are separate from thread priorities.

- IACA – #IOs Init After Completed After – unclear what this really means

- IACB – #IOs Init After Completed Before – this measures how many I/Os ‘jumped the queue’ and were serviced before the current I/O despite being submitted after. This is an optimization that improves throughput (by minimizing seeking) but can hurt the latency of some requests

- IBCB – #IOs Init Before Completed Before – see the comment below that explains this

- QD/C – Queue Depth at Complete Time – this measures how many I/Os were queued up when the current I/O completed

- QD/I – Queue Depth at Init Time – this measures how many I/Os were queued when the current I/O was requested – deep queues imply a saturated disk, which may slow down your disk I/O

- Annotation – this, column, which is available on most or all WPA tables, can be filled in during trace analysis. See this post for more details.

Columns for miscellaneous:

- Source – I have only seen this column be ‘Original’ or ‘Unknown’ and I don’t know what it indicates. Sorry.

- Boosted – unknown

- Table – the name of this table

- Thread Activity Tag – unknown

- Trace # – which loaded trace is being displayed

Sample Summary Tables

Effective use of summary tables requires rearranging the columns to answer whatever questions you may have. Below I have screenshots of some sample rearrangements. If you have particular favorites then you can add these to WPA for easier reuse.

This summary table groups the number and size of I/Os by disk number and by read/write, to get a high-level view of what is going on.

Here we can see a bunch of disk I/O during Windows Live Photo Gallery startup – grouped by process and Path Tree, and sorted by Init Time. This lets us see that WLPG does a lot of small reads to random locations in this one file, which is why it can take a minute or longer to start.

Many other useful arrangements are possible – experiment to see what works.

Learning how to fish

The lack of comprehensive official documentation can be frustrating, but in some cases this problem can be easily worked around. When writing this post I found a trace with lots of disk I/O and just played around. By dragging a particular column to the very left I automatically got a list of all the values it has in my trace, which is usually enough to let me write about it. I encourage you to fearlessly rearrange columns, both to investigate performance problems, and to determine the meanings of unknown columns.

Sometimes there is an apparent mathematical relationship between columns, such as the one between Init Time, Complete Time, and IO Time. When you suspect a relationship and want to test your hypothesis it can be very useful to select a few hundred rows of data, then right-click and use Copy Selection. You can then paste it into Excel and do a few quick calculations.

Pingback: The Lost Xperf Documentation–CPU sampling | Random ASCII

Pingback: The Lost Xperf Documentation–CPU Scheduling | Random ASCII

Pingback: New Version of Xperf–Upgrade Now | Random ASCII

Pingback: Bugs I Got Other Companies to Fix in 2013 | Random ASCII

Pingback: The Lost Xperf Documentation–CPU Usage (Precise) | Random ASCII

Pingback: ETW Central | Random ASCII

WLPG reads – I found exactly this issue right before we shipped… 2 weeks before. With a modest database and an HDD you could be subject to 60s of startup time (assuming superfetch wasn’t preloading your database). Because of superfetch the issue had gone unnoticed by the whole team for years. The fix was deemed to risky.

Thanks for writing. I’ve been reading since pigs flew.

I guess WLPG won’t be getting a fix for this now? If there’s any development going on I’ve got a few other bug reports…

It’s weird that this database issue keeps showing up. VS has the exact same issue (I think they hacked around it by pre-reading the database). I thought databases were supposed to be fast.

I’m afraid I left in 2011. I assume the team is busy making Windows look good at photos in other ways.

IBCB – IO’s Init Before Completed Before. This is the number of IO’s that were initialized before the selected IO and completed before this IO finished. So if your process did two IO’s back to back and the storage responded back in the order requested, the second IO would have 1 IBCB because the first IO was initialized first, was still active while the second one was initialized and completed before the second one completed.

Thanks! I updated that section to mention that there’s more information down here.

Hi, have you ever used VolumeManagerInfo events from SPLIT_IO provider? It seems that there is a bug on it or maybe I’m missing something.

When tracing I/O on a raided volume the requests are broken into many others at disk level and IRPs change, split_io events should connect all these child IRPs to the parent one. Unfortunately what happens is that child’s IRP is always equal to parent’s IRP and it doesn’t looks like an IRP pointer.

Reference: https://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/windows/desktop/aa964808(v=vs.85).aspx

Commands to capture events on a raided volume:

xperf -on LOADER+FILE_IO+FILE_IO_INIT+FILENAME+DISK_IO_INIT+DISK_IO+DRIVERS+SPLIT_IO -BufferSize 1024 -MinBuffers 16 -MaxBuffers 36 -FlushTimer 0

xperf -d kernel.etl

xperf -i kernel.etl -o xperf_events.csv -symbols

Thoughts?

Sorry, no idea.

What is the difference between File I/O and File Based I/o?

I don’t know. Where did you see File Based I/O?

There is a distinction between File I/O (program calls ReadFile) and Disk I/O (call to ReadFile requires going to the disk).

I want to know if there is a way to find duration for operations(read, write, flush) performed by particular file and the file size within a process.

Sure. Grab a trace, open up the file I/O graph/table, then rearrange the columns appropriately. If you want to group by process and file name then put those two columns first, then the orange bar, and the duration column to the right.

Fearlessly rearranging columns is the answer to most ETW investigative questions.

Note that at disk level (and even file level) much of the IO will be listed against System rather than the application itself, due to filecache activity. Usually the first io will be again the application (and/or the antivirius engine)

Note2 – File IO duration does not include any time in (slow) minifilters. There is a separate storage, minifilters section to look at that

I know that the system process ends up doing a lot of the disk I/O due to read-ahead and lazy writing but I think it is incorrect to claim that *file* I/O will be charged to the system process. So, yes, at disk level, but no to file level.

I noticed when looking at task bar context menu latency that the file I/O graph numbers didn’t match the time spent in ReadFile and wasn’t sure why. minifilter time could account for the discrepancy, perhaps.

I don’t have Mini-Filter Delays by default. If I add the FLT*IO* categories then I get it but then the FileIo size in the trace roughly doubles, which seems excessive. Do you know which FLT*IO* categories I actually need?

Hi Bruce; is there a way to measure response time from ETW using WPA when for example I launch an application like video player to playback a video and the disk responds to it.

If you record an ETW trace then you can see input events so you can see when you launched the video player. You can also see when the process started. You can identify when it starts reading from the file system. Correlating that to when decoded pixels hit the screen can be trickier. In this case I typed ‘Ctrl” as soon as Voice Recorder started responding so that I could see that time in the trace.